http://killercoversoftheweek.blogspot.com/2010/05/brown-out.html

Because It’s What’s Up Front That Counts THURSDAY, MAY 6, 2010

Brown Out

Novelist Carter Brown died 25 years ago this week--which was a pretty slick trick, since he had never actually existed. At least not as a separate corporeal entity.The author’s real name was Alan Geoffrey Yates, and he was born in London, England, on August 1, 1923. Yates served with the Royal Navy during the Second World War, and after the fighting and dying was done, he signed on as a sound recordist at a British film company for two years before moving to Australia in 1948. In Sydney, he worked as a public relations staffer and salesman for what was then known asQantas Empire Airways, but also tried composing short stories for magazines such as Thrills Incorporated, and novel-length “scientific thrillers” for Horwitz Publications, a local book publisher (founded in 1920, and evidently still in business). His early literary efforts were intended for Australian readers. But Yates’ career trajectory and audience changed dramatically in 1951.Toni Johnson-Woods, the author of Pulp: A Collector’s Book of Australian Pulp Fiction Covers (2004), tells of Yates’ transformation in an article available on the Web:

The persona ‘Carter Brown’ started modestly enough in the Sydney offices of Horwitz Publications in 1951. The company published locally written fiction, specifically comics and soft-covered genre novels--in common parlance, ‘pulp fiction.’ In 1939 the Australian government had established tariffs on American imports that effectively banned American pulps, and local publishers and writers stepped in to fill the fiction void. This produced Australia’s richest publishing decades, 1939-1959; when the prohibitions were lifted in 1959, the local industry died overnight. In its heyday, Horwitz Publications printed up to forty-eight comics and around twenty-four fiction titles--with print-runs of up to 250,000--each month. After the phenomenal successes of the pulp fiction writers James Hadley Chase andMickey Spillane in the United States, the editorial team at Horwitz decided to exploit Australian readers’ appetite for faux American ‘gangster’ fiction and approached Alan Geoffrey Yates ... [Yates] was asked if he would be interested in writing a mystery series as ‘Peter Carter Brown’; he signed a thirty-year contract which required him to produce two novelettes and one full-length novel a month, and for which he was to receive a guaranteed weekly advance of 30 [pounds sterling].In September 1951 The Lady Is Murder, by Peter Carter Brown, appeared in Australia; seven years and millions of copies later, Horwitz Publications sold the overseas rights to reprint Carter Brown novels to an American publisher, Signet. Over a period of thirty years, from the early fifties to the early eighties, Yates wrote approximately three hundred Carter Brown novels. In the process, he became Australia’s best-selling novelist: Signet claimed international sales of eighty million copies, and the series was translated into more than a dozen languages.

Three hundred books? That’s approaching Georges Simenon’s phenomenal output. It’s no wonder, then, that although Yates enjoyed his increase in pay (£30 was almost double his Qantas salary), he found his writing pace for Horwitz rather grueling. Just looking at the lists of

works he churned out in 1951-1956, 1957-1963, and 1964-1985 might make a normal wordsmith dive to join the dust bunnies under his bed. As Johnson-Woods explains in another essay, this one available on the Mystery*File site:

works he churned out in 1951-1956, 1957-1963, and 1964-1985 might make a normal wordsmith dive to join the dust bunnies under his bed. As Johnson-Woods explains in another essay, this one available on the Mystery*File site:

In 1955 Yates wrote 20 books, the following year 25 appeared--like [fellow Aussie pulp fiction writer Gordon Clive] Bleeck he was writing a new novel every fortnight. In 1960 Lyall Moore of Horwitz calculated that Yates had published about eight million words: “but to get there he has probably written twice the number.” Given Yates’ ability to write 40,000 words overnight, Horwitz were confident when they signed a contract with Signet for Yates to produce one new novel per month. He had been writing that for the past several years.Who didn’t see that no one could plot, write, and edit one 127-page novel a month? Especially when the writer lives in Sydney, has to submit his mss [manuscript] to local editors (at Horwitz), who then edit and send [it] off to Signet. Signet editors then revised the mss and sent [it] back to Horwitz for approval; Horwitz sent the material back to Yates. It was a pretty straightforward but time-consuming [arrangement]. Often Yates’ material did not receive his approval, naturally. Soon Yates was behind and more than a little peeved. Signet had made “a new novel a month” the cornerstone of their Carter Brown publicity. The Signet archives are filled with correspondence that reflects the constant treadmill of late mss and attempts to fill the voids.

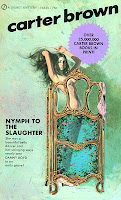

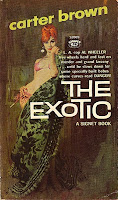

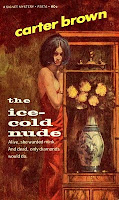

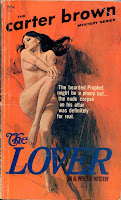

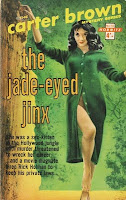

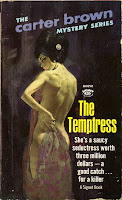

As a result of this regimen, the Carter Brown books were pretty uneven in quality. At their best, they could be likened to novels produced by such contemporaries as Richard S. Prather, Frank Kane,Harold Q. Masur, and Robert Leslie Bellem. Yet William L. DeAndrea, in Encyclopedia Mysteriosa, characterizes them as “fun and forgettable.” A number of the Carter tales were standalones; but Yates also served up several continuing leads, among them Hollywood private investigator Rick Holman (“savior of blackmailed film starlets”), New York-based detective Danny Boyd, hard-drinking Southern California homicide cop Al Wheeler, and “torrid blonde private eye” Mavis Seidlitz. These revolving protagonists helped to differentiate the books from one another; the plots themselves might have worked fine with any of Yates’ sleuths at the helm.Even at the height of their popularity, recalls novelist James Reasoner, the Brown books “didn’t get much respect.” (This, despite the fact that one of Yates’ editors at Signet was the now-famous litterateur, E.L. Doctorow.) That lack of acclaim hardly mattered, however. The books “just sold and sold and sold some more,” Reasoner notes. At various stages, Signet claimed to have 20 million, 40 million, and 50 million Carter Brown books in print. During the 1960s, every drug store, bookstore, and newsstand seemed to have been invaded by slim paperbacks with the byline “Carter Brown” angled across their tops. And it’s said that Brown/Yates was an even bigger sensation in Europe than he was in the United States.Ignoring his British roots and his residency Down Under, Yates set his stories in America, mostly in California. And he attributed  his publishing success to his ability to “think like an American,” even though he never quite understood exactly how to use Yankee slang.Reasoner, meanwhile, credits the popularity of these works to their provocative plots and racy dialogue. “The fact that they were often pretty funny, sometimes had surprisingly complex mysteries, and read extremely fast probably had something to do with it, too,” he remarks. It hardly seemed to matter to readers that, as the Web site Books and Writers points out, “The plots have turns that are not very believable. In one story a nightclub is used as a distribution center for drugs. The stripper hides heroin into her G-string and swaps it during her performance for a buyer’s tie in which the payoff is sewn into the lining.” In another book, Good Morning, Mavis (1957), the curvaceous Ms. Seidlitz “travels to New Orleans, where she is kissed several times during Mardi Grass festival and proposed [to] once. Her client is killed and becomes a zombie--or so Mavis believes. She is kidnapped by a monk and a jester and then saved by an undercover detective from the district attorney’s office.” So long as Yates stuffed his yarns with “action, wisecracks, coarse humor, [and] plenty of voluptuous un- and underdressed sexpots,” to quote Art Scott, readers forgave him his literary faults.What really helped the Carter Brown novels to leap from shelves into the deep pockets of lonely men and teenagers who hadn’t yet experienced any of the acts so available to Yates’ protagonists, though, were their covers. Those covers promising wanton redheads and winsome nymphomaniacs. The covers with the busty women challenging their bikinis’ architecture, and young lovelies with smoky looks and impossibly long legs and nothing but the barest suggestion of fabric (at best) to conceal their shapely asses. The covers with the spicy, playful titles: The Bump and Grind Murders, Nymph to the Slaughter, Nude--With a View, The Pornbroker, Blonde on a Broomstick, The Plush-Lined Coffin, The Myopic Mermaid, The Girl Who Was Possessed. The covers by American artists such as Ron Lesser, Barye Phillips, and Robert McGinnis. Especially Robert McGinnis, whose Carter Brown book fronts became as recognizable as those he illustrated for Brett Halliday, M.E. Chaber, and Edward S. Aarons. (The cover atop this post, from Long Time No Leola [1967], is an excellent example of McGinnis’ art.) The best of the Brown jackets appeared during the 1960s; a decade later, new editions were carrying much less eye-popping photo fronts.I won’t attempt to feature all of the Carter Brown jackets here, just a few of my favorites (click on the covers for enlargements):

his publishing success to his ability to “think like an American,” even though he never quite understood exactly how to use Yankee slang.Reasoner, meanwhile, credits the popularity of these works to their provocative plots and racy dialogue. “The fact that they were often pretty funny, sometimes had surprisingly complex mysteries, and read extremely fast probably had something to do with it, too,” he remarks. It hardly seemed to matter to readers that, as the Web site Books and Writers points out, “The plots have turns that are not very believable. In one story a nightclub is used as a distribution center for drugs. The stripper hides heroin into her G-string and swaps it during her performance for a buyer’s tie in which the payoff is sewn into the lining.” In another book, Good Morning, Mavis (1957), the curvaceous Ms. Seidlitz “travels to New Orleans, where she is kissed several times during Mardi Grass festival and proposed [to] once. Her client is killed and becomes a zombie--or so Mavis believes. She is kidnapped by a monk and a jester and then saved by an undercover detective from the district attorney’s office.” So long as Yates stuffed his yarns with “action, wisecracks, coarse humor, [and] plenty of voluptuous un- and underdressed sexpots,” to quote Art Scott, readers forgave him his literary faults.What really helped the Carter Brown novels to leap from shelves into the deep pockets of lonely men and teenagers who hadn’t yet experienced any of the acts so available to Yates’ protagonists, though, were their covers. Those covers promising wanton redheads and winsome nymphomaniacs. The covers with the busty women challenging their bikinis’ architecture, and young lovelies with smoky looks and impossibly long legs and nothing but the barest suggestion of fabric (at best) to conceal their shapely asses. The covers with the spicy, playful titles: The Bump and Grind Murders, Nymph to the Slaughter, Nude--With a View, The Pornbroker, Blonde on a Broomstick, The Plush-Lined Coffin, The Myopic Mermaid, The Girl Who Was Possessed. The covers by American artists such as Ron Lesser, Barye Phillips, and Robert McGinnis. Especially Robert McGinnis, whose Carter Brown book fronts became as recognizable as those he illustrated for Brett Halliday, M.E. Chaber, and Edward S. Aarons. (The cover atop this post, from Long Time No Leola [1967], is an excellent example of McGinnis’ art.) The best of the Brown jackets appeared during the 1960s; a decade later, new editions were carrying much less eye-popping photo fronts.I won’t attempt to feature all of the Carter Brown jackets here, just a few of my favorites (click on the covers for enlargements):

(Interested in seeing more? Click here, here, and here.)While Alan G. Yates never attained the critical respect enjoyed byThomas B. Dewey, Talmage Powell, John D. MacDonald, or others; and he never had the impact on the genre that somebody like Mickey Spillane did, he was at least acknowledged for his immense body of work. In 1997, the Crime Writers’ Association of Australia bestowed upon him its Lifetime Achievement Award. Unfortunately, Yates wasn’t around to receive that honor. The man once known as Carter Brown died on May 5, 1985.READ MORE: “Toni Johnson-Woods on the Carter Brown Mystery Theatre” (Mystery*File); “Fiction: Carter Brown--None But the Lethaland The Tigress,” by Bryin Abraham (Mostly Crappy Books); and Bookgasm’s Bruce Grossman has reviewed a number of the Carter Brown novels.

(Interested in seeing more? Click here, here, and here.)While Alan G. Yates never attained the critical respect enjoyed byThomas B. Dewey, Talmage Powell, John D. MacDonald, or others; and he never had the impact on the genre that somebody like Mickey Spillane did, he was at least acknowledged for his immense body of work. In 1997, the Crime Writers’ Association of Australia bestowed upon him its Lifetime Achievement Award. Unfortunately, Yates wasn’t around to receive that honor. The man once known as Carter Brown died on May 5, 1985.READ MORE: “Toni Johnson-Woods on the Carter Brown Mystery Theatre” (Mystery*File); “Fiction: Carter Brown--None But the Lethaland The Tigress,” by Bryin Abraham (Mostly Crappy Books); and Bookgasm’s Bruce Grossman has reviewed a number of the Carter Brown novels.

McGinnis is the artist for this particular cover

ReplyDelete